On this page:

SUBSEQUENT DEVELOPMENT

CLASS STRUCTURE

LIFE IN QUARANTINE

RMS HIMALAYA

THE CENTURY’S END

Next Page: – The Fourth Phase 1900 to 1925

Subsequent Development – The Third Phase: 1876-1899

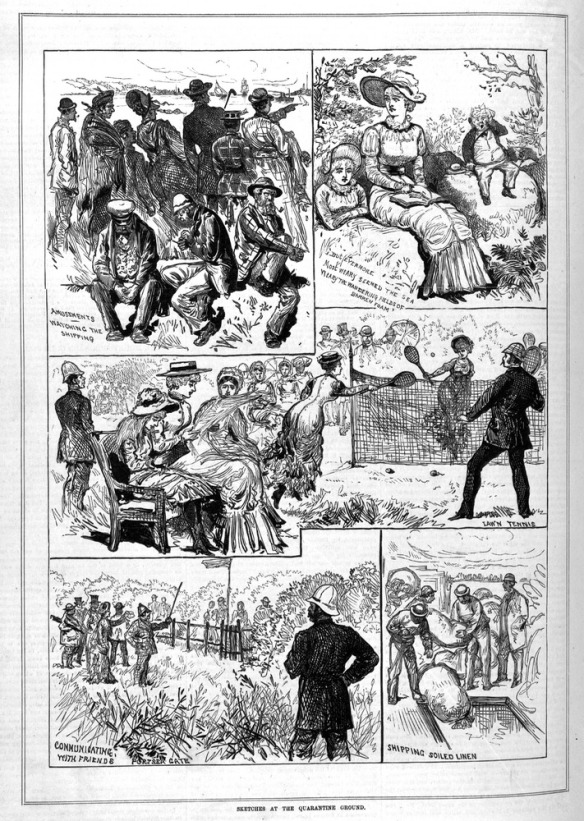

Early in 1874 telegraphic communications were established between the station and Melbourne. Prior to this, messages had to be taken by boat to Queenscliff for relay to Melbourne. Initially the installation of the service was viewed by residents of Queenscliff who feared that disease could also be transmitted by the wires. It is assumed these fears were swiftly allayed. The introduction of the service meant that relatives and friends of passengers were quickly alerted when ships were detained and communication could be made with the unlucky incumbents.58 Many people subsequently visited the station boundary, as previously, calling out to their relatives and friends, and the arrangements were the subject of several amusing images in later years. The Australasian Sketcher published a series of engravings outlining some of the activities undertaken by the unlucky passengers of the Garonne, detained at Point Nepean in January 1882, due to an outbreak of smallpox to while away the time.59

At this date, and as the sketches below illustrate, visitors could call from quite a close distance, supervised by a police officer. In later times a double fence arrangement enclosing a forty foot ‘no man’s land’ was imposed.

In May 1874, the area was struck by a violent storm which caused damage to the station buildings. The Superintendent James Walker initially telegraphed to the Chief Medical Officer, then followed this communication with a letter which gave an outline of the damage:

At daylight the gale seemed to be at its worst. At this time nothing had gone wrong with the buildings but between 9 and 10 o’clock half of the drying house verandah was blown down and the ridging of the wash house lifted. Directly afterwards about sixty feet of lead and numerous slates were blown off the main roof of no. 4 Hospital and some sheets of zinc off the balcony roof …. while myself and the men were trying to secure the remaining portion of the drying house verandah from being blown down, nearly the whole of the lead was stripped off the main store, carrying with it a portion of the zinc roofing. At one time it seemed impossible to prevent the whole roof being blown into the sea, but by working in the storm we managed to prevent any further damage being done to it.60

Damage to the buildings was painstakingly repaired over the following months.

Over the next couple of decades, some changes to the station buildings were undertaken and a few new buildings were also constructed.

Class Structure

Initially the hospital buildings were not allocated or arranged in accordance with the class structure of the vessels in which the passengers had travelled; those who were ill or showing signs of the effects of disease were accommodated in the hospitals on the rise while first class passengers detained for precautionary reasons were, at least until 1864, usually accommodated aboard ship. The second and steerage class passengers who were retained for precautionary reasons were accommodated in the three hospital buildings on the flat.

Subsequently the buildings were allocated along class lines with Hospital No. 1 being occupied for first class passengers and included a dining room and ante-room for use of the residents; the adjacent Hospital No. 2 was for second class passengers who ate in their rooms. Hospital Nos 3 and 4 on the flat were for steerage class passengers who also took meals in their rooms. Following these changes in use, Hospital No. 5 consequently became the isolation hospital where those afflicted by disease were accommodated, again taking their meals in their rooms.

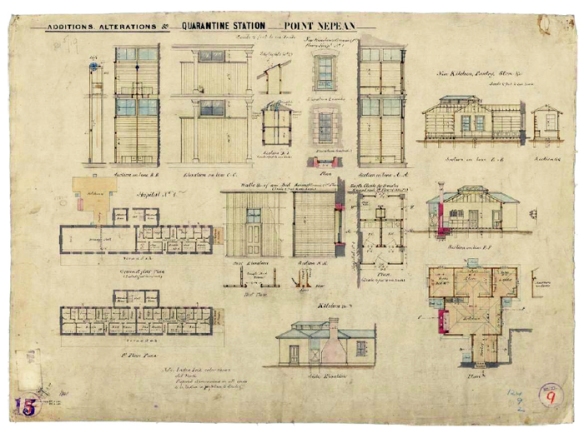

In the mid-1880s Hospital No.5 was formally converted for use as an Isolation Hospital, with lavatory and laundry additions to the building as well as the construction of a free-standing timber kitchen building.

A number of changes were also made to Hospital No. 1 for its conversion to first class passenger accommodation. To this end, in 1884, a new kitchen building was constructed behind the hospital, and the internal layout was altered to provide separate bedrooms and a dining hall on the ground floor. Lavatories (earth closets) were appended to the southern end of the building, infilling the verandah (See below). In 1889 a cottage for the boatman was erected near the entrance gate.

Additions and alterations to the Quarantine Station, June 1884.

This drawing details the conversion of Hospital No. 1 for first class accommodation.

Source: National Archives of Australia.

Additions and alterations to the Quarantine Station, June 1884.

This drawing details the conversion of Hospital No. 1 for first class accommodation.

Source: National Archives of Australia.

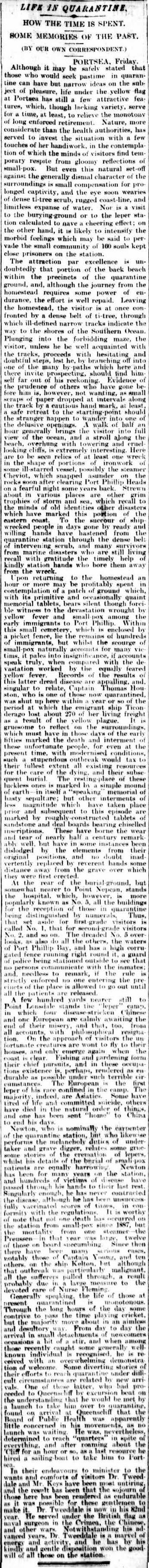

Life In Quarantine

This Article Appeared in The Argus of 23 Feb 1897 describing Life In Quarantine:

From Trove HERE

RMS Himalaya

Despite these works, a serious incident in 1897 would test the station, exposing weaknesses in its dealings with quarantine detainees and subject it to significant criticism. In April 1897, Dr. Couper Johnson, at that time Superintendent of the station received notification by telegram that the RMS Himalaya had been boarded in Adelaide and a single case of smallpox had been identified. Over following days the number of passengers and crew to be landed grew in number until over 100 people – a combination of first class, second class and stevedores as well as several stewards to assist – descended on the station on the evening of Wednesday 21 April.

The Argus on the following Monday published a letter written by Lieutenant-Colonel A Sadler, one of the offloaded passengers, outlining in detail an account of the reception afforded to passengers at the station. The letter described many shortcomings, including the lack of dining facilities for second class passengers who ate in the anteroom to the first class dining room, and Dr Johnson’s refusal to allow passengers to have access to their baggage to collect night attire, until threatened by an immediate telegraph to The Argus (at which point he acquiesced).

Perhaps most damning, especially in the light of efforts to improve hygiene and counter the spread of disease in the years after the first Australian Sanitary Conference of 1884, the letter also noted:

There was no water in many of the rooms and no soap. In some rooms there were pieces of soap left by the last occupants (presumably the Ninevah passengers), so that not only do the officials not take the necessary steps to prevent sickness, but by their gross carelessness actually do their best to cause an outbreak.61

A flurry of official communications resulted in Dr Johnson being forced to explain his actions and to address a series of issues raised by the detainees. While the fracas ended with many detainees signing a letter in support of Dr Johnson, the issues of lack of decent accommodation and facilities which allowed a degree of comfort to all, regardless of their shipboard ‘class’ and improved facilities for disinfection of property and person would need to be addressed. Part of the problem may also have stemmed from the enforced period of detention (and boredom) as those vaccinated were held until their results were returned.62

The Century’s End

The last building to be erected on the station in the 19th century was actually the third to have been built for the purpose of housing the Medical Superintendent (Below) and once again appears to have incorporated parts of the earlier structures.