On this page:

THE FIRST BUILDINGS EARLY 1850s

DISPOSAL OF THE DEAD

CURTAILING THE UNLUCKY

FURTHER DEVELOPMENT

Next Page: – Quarantine the Second Phase 1856 to 1875

A Reactionary Establishment – the First Station Buildings: Early 1850s

First steps Construction of the first buildings at the new quarantine station was a drawn-out process: despite Ferguson’s initial assessment, there was a lack of locally-cut sawn timber, much of which had been burnt by the lime burners and had not grown back. This meant that sawn timber had to be brought to the site, thus slowing the building process. On 25 April 1853 the Argus recorded the commencement of the building works:

Sanatorium: Our readers will not probably be aware that, for some time past, arrangements have been in hand for the establishment of a quarantine establishment at the heads. Formerly there was nothing but a bare station indicative of the spot where vessels were to lie and where only persons might land who had a foul bill of health.

But now some attempt is being made to step in advance of the antiquated system by which unclean people were merely to be avoided, not to be cured.

A hospital with fever wards is in process of erection and a resident medical officer has been appointed and is now on the spot. The buildings will include officers’ quarters, the hospital above mentioned, stores, etc. They will be erected partly of timber and partly of the stone found near the spot, a kind of bastard freestone, not valuable, but sufficiently good to be used when it costs nothing but the quarrying expenses, as in the present instance. The site is in the neck of the promontory headed by Point Nepean and includes two sea frontages — one to the open straits and the other to the bay. The latter is the site of the establishment, the limits of which will be marked by the quarantine flag, all yellow.17

William Walker was in residence at the station when this article was published. His journal entry outlined the primitive nature of the living conditions enjoyed at the station by its hapless inmates, which were rather in contrast to the orderly account published in the Argus:

They are about starting a Hospital, Doctors house and houses capable of holding 200 people all to be built of wood. We are to have 5 shillings per day during the time of our quarantine which will last 6 weeks from the 7th of April. After that the carpenters that are hear [sic] which is only 3 are to have town wages which is 25 shillings per day. Then we shall have to find our own provisions which will cost about 20 shillings per week. We shall have no wood or water to buy and still have our tent to live in.

You must understand we have had to live in tents ever since we came here. When we came on shore we thought we should be comfortably housed according to our doctors account with plenty of vegetables milk and eggs and other niceties but soon found we had to lead a regular bush life. The first thing we had to do after landing was to pitch the tents. They are about 12 feet by 10. Most of us have one to ourselves. After the tents were pitched it was getting towards tea time so off we had to go in the bush and cut our wood which is plentiful enough and make a regular Gipsies fire. We have a very good supply of water from a well close to our tents which we are obliged to boil it before drinking or else we should have dysentery.18

From this account it is suggested that progress on the erection of the hospital building was a slow undertaking. A return of the buildings and lands at the Sanitary Station in August 185419 indicated that more than a year later, the three buildings which had commenced construction in March 1853 – the wooden hospital, a two-roomed wooden house and the stone store house – were all still unfinished.20

The new stone store house was positioned on the ‘flat’, near to the stone dwelling requisitioned from Patrick Sullivan.

The timber hospital building was erected atop the bluff, in the vicinity of the subsequent Hospitals Nos 1 and 2. It later served as a bedding store, once the present hospital buildings were erected.

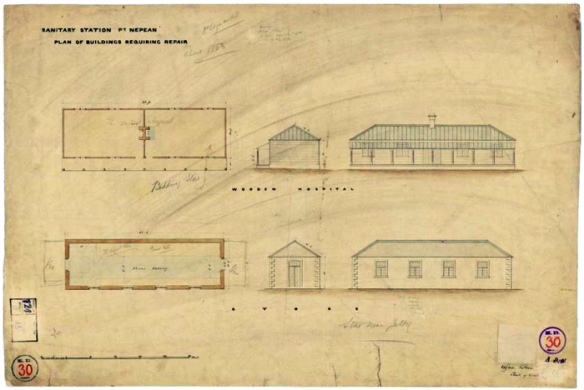

An 1856 drawing (below) depicts both these buildings as requiring repair, indicating that the climate and conditions had, in a comparatively short time, already taken a physical toll on the buildings.21 The drawing was signed by Alfred Scurry, Clerk of Works in the Geelong office.

Disposal of the dead

The lack of availability of sawn timber was to have another ramification – the issue of the disposal of the dead. J H Welch in his history of the Quarantine Station outlined some of the mitigating circumstances.

The lack of sawn timber which delayed construction of buildings also restricted the manufacture of coffins. The fears of the healthy who wished to remain so were not conducive to the production of grave diggers, so difficulty was experienced in disposing of bodies. A cemetery 175ft. by 115ft. was finally established near the water’s edge inside the Station and those who died were interred as suitably as circumstances permitted by their relatives, friends, or such men as were prepared to work as grave diggers.22

The difficulty of disposal made the emotional response to the death of loved ones all the more painful. William Walker’s son John had died of whooping cough aboard the Confiance in April 1853:

I am sorry to say our Dear Child John had the cough which proved fatal to him. The poor little fellow laboured under the distressing disease for 6 weeks…. not even the Burial service read over the dead nor a coffin to put them in. Our poor little John was the first that had a coffin out of about a hundred that had been buried in the ground and that was quite against the rules but we were determined to have one so of course we had it.23

It is also noted that no account found to date has referred to the presence of any form of place of worship within the Quarantine Station grounds; it is therefore not known what provision was made for worship or church services on the site.

Curtailing the Unlucky

In April 1854 tenders were called for the delivery of 4000 posts and rails, presumably for the construction of a boundary fence, to prevent unintentional wanderings such as those undertaken by William Walker:

The ground we are on extends along the sea beach. It is called Point Napene [sic] Port Phillip Head. We have about 8 or 10 miles to stroll about on. At each end of the quarantene ground there is a yellow flag that is our Boundry [sic] post but some of us often make a mistake and go miles beyond up towards Melbourne. There is no other road to go for we have the sea at one end and both sides of us.24

A further preventative measure was the location of a permanent police presence at the station grounds, something that had been anticipated by Captain Ferguson in his communication to Governor La Trobe during the Ticonderoga incident. He had recommended that:

A Sergeant and a small body of police be sent overland and stationed at the Eastern boundary of the quarantine ground to maintain order, and to check the insubordination which was beginning to show itself amongst the seamen and Emigrants before I left.25

Further development

In August 1854 Dr James Reed took up the position of resident doctor, succeeding Dr Williams, and James Walker had been appointed Storekeeper for the station. Buildings at this time included a timber doctor’s house, the timber hospital, stone cottage, Sullivan’s preexisting stone cottage, and imported prefabricated iron houses for use by the police, who were to be accommodated at the eastern boundary of the station, and a form of jetty. The stone store, placed near to the entrance to the jetty was nearing completion at this time.

The Station in this period could accommodate 450 persons under canvas and fifty in the hospital on forty iron bedsteads. Those in tents had no beds, but were raised above the ground by means of wooden sleeping platforms, received in April 1855.

The wooden hospital building was proving to be inadequate and Dr Reed requested that it be extended. His request was rejected by the Government but was told that any resubmission in 1856 would be favourably considered. At this time there was a degree of careful consideration of the placement of more permanent structures. The further development of the station would now be guided by a sense of deliberation and order, in contrast to the initial establishment phase, which had been characterised by a reactive approach in the face of the Ticonderoga episode, and subsequent events.